While working on the Just Use Postgres book, I kept running into conversations and content where folks were asking for advice or explaining how to use Postgres for analytics. If I had bumped into such discussions in the early 2020s, I would have laughed it off and passed by. Back then, I knew Postgres as a relational database optimized for transactional workloads, and reading about using Postgres for analytics would have looked odd to me, to say the least.

But it was 2025, and I was writing the book which helped me personally rediscover the database. That year, I was no longer surprised to hear that someone was using Postgres for analytical workloads. Quite the opposite, I was curios to learn how they do that. But, I didn't have the time to learn how exactly Postgres could function as an analytical database, nor was there any space left to cover this topic in the book. So, I carried on with the book's material but decided to study the analytical landscape later.

Luckily, the book is now published, and I finally have time to explore what Postgres for analytics really means and how the database can be used for this use case.

What to expect from this article

With this blog post, I'm not going to discuss how to use materialized views, indexes, partitioning, and other built-in Postgres capabilities to get the database working for analytical workloads. That's because those capabilities are typically used to optimize Postgres for a pre-defined set of analytical queries your application is supposed to execute. And the thing is, if you know how Postgres is going to be used, then you can optimize it for pretty much anything, including analytics.

The goal of this article is to give a high-level overview of how Postgres can be used for ad-hoc analytical workloads. With ad-hoc queries, you can't know in advance how exactly the data is going to be accessed. There is no pre-defined list of analytical queries that can hit your database. It's up to the application and end user to decide what, when, and how to retrieve.

Thus, I'll provide a high-level overview of how Postgres can be used for, or become a part of, ad-hoc analytical workloads. Note that I'll discuss several particular solutions along the way with no purpose of comparing them directly or showing that one is better than the other. I aim to walk you through existing options so that you can choose the one that works best for your use case. With that, let's go.

These are the ways

There are not one, not two, but at least three different ways you can use Postgres for ad-hoc analytics. You can think of each way as a distinct category of solutions that enables the database for analytics one way or another.

These are the three ways:

- Postgres with a built-in columnar store - solutions from this category add a columnar storage engine to Postgres, which allows you to efficiently store and query analytical datasets without leaving the boundaries of the database. TimescaleDB (TigerData) and Hydra Columnar are examples of extensions from this category.

- Postgres as a query/compute engine - another option is to keep analytical data in a specialized analytical database or lakehouse and use Postgres as a query engine that can easily connect to that external system and query data from there. The pg_duckdb, pg_lake, and pg_clickhouse extensions allow you to achieve exactly that.

- Sync from Postgres, query from an analytical store - sometimes the best analytics strategy is neither to store nor to query analytical data from Postgres. Instead, Postgres can sync its data in real time to an external analytical database or lakehouse, and then you can query that external system directly (bypassing Postgres) using its own ecosystem of tools and services. To make this approach work, you need a replication/CDC solution that can capture changes from Postgres and apply them on the analytical store side. Supabase ETL, Fivetran, and Decodable are a few examples from this category.

Now, let's explore each category in more detail.

First Way: Postgres with a built-in columnar store

As the name of this category suggests, you can advance Postgres for analytical workloads by enabling a columnar storage engine. With such an engine, the database can arrange data in a columnar format, which is better suited for ad-hoc analytical queries.

When should you consider using this approach?

- You and your team are already familiar with Postgres and would like to continue capitalizing on that experience instead of learning another specialized analytical solution.

- You don't have a dedicated lakehouse or analytical store, or are not planning to introduce one. All you need is for Postgres to support ad-hoc analytical queries over its own historical and operational data.

Next, let's look at the following animated diagram to refresh our understanding of how a row store differs from a columnar one, and why the latter is more efficient for ad-hoc queries:

The diagram assumes you have a table storing user data across the id, name, age, and city columns. Next, you execute the SELECT max(age) FROM users query to find the oldest user in the database. This is how such a query is executed if the data resides in a row or columnar store:

- The row store keeps rows of data one after another in blocks on disk and pages in memory. Even if a query needs to access the value of a particular column (such as

age), the row store still needs to retrieve an entire row before the database can access the column of interest. The diagram shows how the row store loads all the records from disk first (with all four columns) and only then reads the values of theagecolumn. - The columnar store keeps values of a particular column (such as

age) one after another, both on disk and in memory. This allows it to query only the values of the column(s) of interest and avoid loading values from other columns that might exist in your dataset. The diagram shows how the columnar store can access the values of theagecolumn directly by loading a particular file with those values from disk or accessing a specific memory segment with the required data. Because of the way the data is arranged in a columnar store, the database doesn't have to rely on traditional indexing for ad-hoc analytical queries and can instead exploit other optimizations, including vectorized execution (SIMD - single instruction, multiple data) and compression.

Now, getting back to Postgres which comes with a row-based storage engine optimized for transactional workloads. The database doesn't support a columnar store out of the box, but this can be easily addressed by using one of its extensions.

TimescaleDB is one such extension which is widely known and used for time-series workloads. The extension supports a hybrid row-columnar storage engine called Hypercore.

Hypercore adds new records to the row store, which is optimized for fast updates and point queries over a small subset of the records. Over time, some data "ages" and becomes more suited for analytics. Such data is automatically converted into a columnar format which lets you aggregate, scan, and efficiently perform other analytical operations over large volumes of data.

For an in-depth overview of how Hypercore is implemented and functions, refer to the Data Model page.

Hydra Columnar is another Postgres extension that adds a columnar store to the database. However, the extension no longer seems to be in active development, with the last updates dated in 2024. Thus, if you decide to choose Postgres with a built-in columnar store for your analytical workloads, you should be better off with TimescaleDB.

Second Way: Postgres as a query/compute engine

If your historical data is already stored in an analytical database or lakehouse, and you'd like to continue keeping it there, then you can use Postgres as a query (aka. compute) engine that transparently connects to the external system and queries data which Postgres doesn't own.

When should you use this approach?

- You already store large volumes data in a columnar database, lakehouse, or object store in Parquet files, Iceberg tables, or other formats optimized for ad-hoc analytical queries. You already have apps, tools and services accessing the analytical store directly and there is no real need to keep a copy of the data in Postgres.

- You prefer querying an external store directly from Postgres instead of learning and introducing additional tools.

- You need to query and join operational data owned by Postgres with historical data located in an external store.

There are several extensions out there that can turn Postgres into a query engine capable of querying remote analytical data. Some, such as pg_duckdb, pg_lake, and pg_mooncake, integrate Postgres with DuckDB, where the latter is in charge of querying data residing in a lakehouse or analytical store. Others, such as pg_clickhouse, integrate Postgres with a particular analytical database like ClickHouse and let Postgres query it directly.

Let's review two extensions from this category - pg_duckdb and pg_lake - to better understand how exactly Postgres can query analytical data when it doesn't own it.

pg_duckdb: embedding DuckDB into Postgres

The pg_duckdb is an extension that embeds DuckDB into Postgres.

If this is the first time you hear about DuckDB, then all you need to know is that it's an open-source lightweight analytical database engine that can run within your application process. And what the creators of pg_duckdb discovered is that that application process can also be a Postgres backend process (which handles queries of a particular client connection), and eventually they went ahead and embedded DuckDB into Postgres.

The DuckDB instance running inside of Postgres can query both Postgres's tables as well as external Parquet files, Iceberg tables, Delta datasets, and other types of data stored in different formats.

For example, the following query shows how Postgres can use the iceberg_scan function of the pg_duckdb extension to query an Iceberg table storing historical market data for a particular period and calculate the average price for Disney's ticker:

SELECT AVG(i['price']) AS avg_price

FROM iceberg_scan('data/iceberg/market_data') i

WHERE i['ticker'] = 'DIS';The query passes the location of the target Iceberg table to the iceberg_scan function and uses i as an alias for the function call. The fields from the table are accessed using the i[column_name] notation. The data is filtered by the ticker name and the query calculates the average price for Disney.

The i[column_name] notation should become optional in future releases of pg_duckdb. There is work in progress that would let you access column values directly (the same way you access columns in regular Postgres tables).

The extension also lets you join transactional data stored in a Postgres table with a historical dataset located in an external analytical store. The next query shows how to calculate unrealized profit and loss (PnL) for all open Disney positions in user portfolios, assuming the positions are closed (sold) at the average price computed from the historical dataset.

WITH market_data AS (

SELECT AVG(i['price']) AS avg_price

FROM iceberg_scan('s3://data/iceberg/market_data') i

WHERE i['ticker'] = 'DIS'

)

SELECT

p.id, p.ticker,

p.shares * (m.avg_price - p.cost_basis) AS unrealized_pnl

FROM portfolio p

CROSS JOIN market_data m

WHERE p.ticker = 'DIS' and p.status = 'open';First, the query calculates the avg_price for the Disney ticker over the historical dataset stored in the Iceberg table. After that, the query accesses user portfolios stored in Postgres's portfolio table and calculates unrealized PnL for every open Disney position across all portfolios.

Unrealized PnL basically implies What would be my profit or loss if I sold right now?

Now, let's take a look at the following diagram to better understand how such a query is executed in Postgres and what role DuckDB plays during execution:

The query execution flow is as follows:

- An application sends the query to Postgres.

- The Postgres parser transforms the query's SQL string into a syntax tree, which is a hierarchical representation of the query. The pg_duckdb extension then checks this syntax tree before it is passed to the Postgres planner. In our case, the extension determines that the query needs to access the Iceberg table and, as a result, delegates the entire query execution to the embedded instance of DuckDB. Note, that DuckDB will query both the remote Iceberg table and the local Postgres table.

- DuckDB then connects to the lakehouse and loads the requested market data.

- Once the data is loaded, DuckDB joins the historical market data with the portfolio data stored in Postgres.

- Postgres returns the result produced by DuckDB to the client application.

We've only briefly discussed how pg_duckdb can query lakehouse data and join it with transactional data stored in Postgres.

For an in-depth overview of how pg_duckdb is implemented and how it works internally, watch the recording of the pg_duckdb: Ducking awesome analytics in Postgres tech talk by Jelte Fennema-Nio, a key contributor to pg_duckdb.

pg_lake: DuckDB as a sidecar server

pg_lake is a project that combines a set of extensions and components that let you query and modify Iceberg tables, as well as other common lakehouse file formats, directly from Postgres. The project also uses DuckDB to accelerate analytical queries over lakehouse data. However, unlike the pg_duckdb extension, pg_lake runs DuckDB in a sidecar process called pgduck_server, which communicates with the Postgres process during query execution.

There are several reasons why the pg_lake team decided to run DuckDB as a sidecar process instead of embedding it directly into Postgres. These are some of them:

- It's not a straightforward task to integrate Postgres and DuckDB due to architectural and codebase differences. At a minimum, Postgres is written in C, while DuckDB is written in C++. Postgres is a multi-process database, whereas DuckDB is a multi-threaded one.

- The sidecar DuckDB process can be shared and used by multiple Postgres processes serving different client connections. If DuckDB is embedded into Postgres, every new Postgres process created for a new client connection also runs its own embedded instance of DuckDB.

Let's continue using our imaginary market dataset that can be accessed via Iceberg tables and see how pg_lake can accelerate the calculation of unrealized PnL.

First, with pg_lake you create an Iceberg table using the regular CREATE TABLE command. All you need to do is add the USING iceberg WITH clause at the end of the table definition.

CREATE TABLE market_data_iceberg ()

USING iceberg WITH (definition_from = 's3://data/market_data_2025_12.parquet');The definition_from option instructs pg_lake to inherit the column definitions from the target file, which will later be queried via the Iceberg table. This is why the table has no explicitly defined columns.

pg_lake implements and manages a full Iceberg catalog within Postgres. Thus, once the Iceberg table appears in the catalog, Postgres can efficiently query and update the lakehouse data transactionally with no dependency on any external catalogs. Moreover, Spark and other Iceberg tools can work with the pg_lake's Iceberg catalog by connecting to Postgres.

Once the Iceberg table is registered with Postgres, you can query it directly and join it with local Postgres tables:

WITH market_data AS (

SELECT AVG(price) AS avg_price

FROM market_data_iceberg

WHERE ticker = 'DIS'

)

SELECT

p.id, p.ticker,

p.shares * (m.avg_price - p.cost_basis) AS unrealized_pnl

FROM portfolio p

CROSS JOIN market_data m

WHERE p.ticker = 'DIS' and p.status = 'open';The market_data CTE is evaluated first. It calculates the average price for Disney stock over the time period available in the market_data_iceberg table. The price and ticker columns were present in the target market data file and were inherited by Postgres at table creation time. Once the average price is calculated, the query computes the unrealized PnL by joining the average price with the portfolio data stored in a regular local Postgres table.

The following diagram shows a how pg_lake executes such a query and the roles DuckDB and Postgres play in the query execution:

The query execution flow is as follows:

- An application sends the query to Postgres.

- Postgres parses the query and determines that the CTE needs to calculate the average price for the Disney ticker using data from the

market_data_icebergtable. Since this table resides in the lakehouse, Postgres forwards this part of the query to pgduck_server for accelerated execution. If the query uses Postgres-specific syntax or functions that DuckDB does not support, pg_lake rewrites those parts of the query into a DuckDB-compatible form. - pgduck_server receives the query from the CTE and delegates its execution to DuckDB. DuckDB queries the lakehouse to retrieve the required market data. If the relevant data is already cached locally from previous executions, DuckDB can reuse it instead of pulling it from the lakehouse again.

- DuckDB computes the average price for the Disney ticker and returns the result to Postgres.

- Postgres joins the calculated average price with the local portfolio data to compute the unrealized PnL.

- Postgres returns the final result to the application.

- The lakehouse returns the requested data.

The caching layer in the pgduck_server component is implemented as an LRU file cache (write-through with background fetches) on top of DuckDB's file system abstraction, which can be activated by running pgduck_server with the --cache_dir setting.

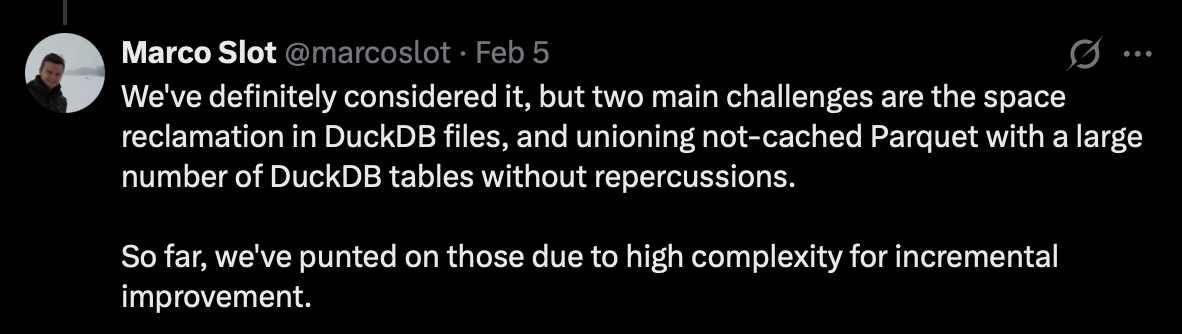

This is how Marco Slot, a key contributor to pg_lake, explains why they implemented a separate caching layer instead of reusing DuckDB's columnar storage:

We've only briefly discussed how pg_lake can query lakehouse data and join it with transactional data stored in Postgres. However, the project supports much more, including the ability to create and modify Iceberg tables transactionally from Postgres and query geospatial formats

For an in-depth overview of how pg_lake is implemented and how it works internally, watch the recording of the Converging Database Architectures DuckDB in PostgreSQL tech talk by Marco Slot.

Third Way: sync from Postgres, query from an analytical store

The third and final option assumes that Postgres is not involved in storing or querying analytical data at all. Instead, the database ships its own data to your analytical store or lakehouse, and you then query that data using specialized tools that integrate with the target analytical system.

When should you use this approach?

- You already have a lakehouse or analytical store that collects data from various sources, and you'd like Postgres to be one of such sources.

- You don't want to run analytical workloads on Postgres at all and would rather rely on specialized analytical systems for ad-hoc queries.

Let's take a quick look at the basic building blocks for the scenario where Postgres becomes part of your analytical solution by shipping its changes to the lakehouse:

- An application modifies data stored in Postgres.

- Postgres persists all changes in its write-ahead log (WAL).

- A replication solution consumes the changes from the WAL via Postgres logical replication or another mechanism.

- The replication solution syncs the received changes to the lakehouse.

- An analytical tool can then be used to query the latest data directly from the lakehouse.

If you need to join Postgres tables with lakehouse data, you can take advantage of federated query capabilities provided by some analytical tools. Federated queries can access multiple data sources, including Postgres, and join the retrieved data to produce a final result. This capability can be handy if you don't sync all Postgres tables to the lakehouse.

With that, we've discussed several ways you can use Postgres for analytics. All of these options have their pros and cons, but the choice is always yours. Pick the one that best fits your use case, and keep an eye on future developments in this area because it feels like Postgres is just getting started with analytics.